Knowing What You Know and What You Don't Know - EF: Metacognition

There is nothing more frustrating than putting a ton of effort into something, and not having it go well.

I remember when I was in college I had a test coming up in a General Education Physics Class. I knew that Physics wasn’t something that came naturally to me, but I was confident in my ability to learn the material. For the first test, I studied for 46 hours. This seems like an exaggeration, but at no point was I able to confidently say “I am ready for this test” and I just kept re-reading my notes and making new lists and charts.

I took the test and couldn’t really tell how it went. When I finally received my grade, I had scored a 42. I could not understand why my grade did not reflect the amount of effort I had put into the class. When I asked my teacher for help, she asked me what exactly I was confused about. I had no answer. I could not pinpoint what I knew, and what I didn’t know. This did not provide any basis for her to help me and I struggled a great deal throughout the rest of the class.

The skill I was lacking was not necessarily the ability to understand physics, but instead the ability to understand what exactly I didn’t understand. This is called metacognition.

Metacognition

By definition, metacognition refers to the ability to assess your knowledge of a topic and understand what exactly you know and what you don’t understand.

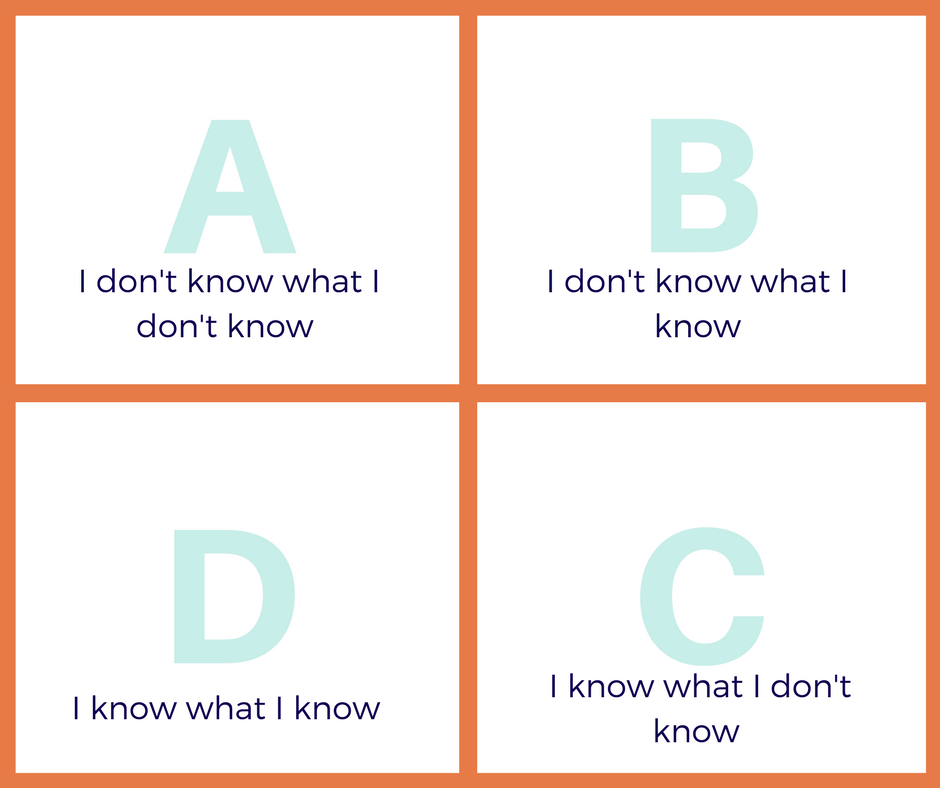

When someone is trying to learn a new concept, there are four possible places they can cognitively be.

A. I don’t know what I don’t know.

This is typically where someone starts when they are being introduced to a new concept. For example, if someone asked you what you didn’t know about Quantum Physics, (unless you, as a reader have studied this in the past) you might say “I have no idea what I don’t know.” This is an okay place to start, but if we want to gain any knowledge about the topic, we need to move out of this area sooner than later.

B. I don’t know what I know.

This means that you do have an underlying understanding of the topic, but you don’t know that you know it. This can be a nice surprise if you answer a question and get it right, but this is not where you ultimately want to be. The downfall to being in this area is that you will not be confident in your knowledge. You will find yourself second-guessing your answers and abilities. This is also not a good place to stay if you would like to master the concept.

C. I know what I don’t know.

This is a great stepping stone in learning. Being able to accurately articulate what you don’t know, gives you the ability to ask questions and seek help as opposed to saying “I just don’t get it.” If you can say “I don’t understand XYZ,” then the person you are asking has a clear idea of what he/she needs to explain and how to help you.

D. I know what I know.

Ultimately, this is where we want to be. This shows mastery of a concept and gives you confidence in your ability.

The best combination of places to be while learning is in C and D. If I had known which physics concepts I understood and which I didn’t, I wouldn’t have wasted 46 hours studying for a test. Instead, I would have been able to get specific help on the questions I had, and I wouldn’t have wasted time studying the things I understood.

Tips to Move out of "Not Knowing What You Don't Know"

Understanding what you don't understand can be a difficult task. Some ways we practice this skill with our kids are...

While reading, have the child highlight words they don't understand.

Use a graphic organizer for writing/math. By working through things step by step, it is easier to pinpoint exactly where mistakes are being made.

Study guides are a great tool when studying for a test. Have your child study first, and then try to fill out the study guide without referring back to notes. For your child to be confident that he/she does, in fact, know something, they should be able to give 3 reasons why they know that they understand it. For example, a student who is confident he/she understands long division would be able to say, “I know that I know it because…

1) I can accurately answer all of the questions in my study guide,

2) I understand the concepts behind why it works,

3) I can teach it to someone else."

After that student takes the long division test, one of two things will happen. Either, the test will go perfectly and the student will receive a high score, or, the score will be lower than the student was expecting going into the test. If the latter occurs, he/she should compare the test to the 3 reasons they outlined above. Take these to the teacher, and see where the breakdown occurred. Maybe the student didn’t understand the concept quite as well as he/she thought. Maybe he/she got test anxiety and performed poorly. Whatever the cause was, by following this process it will be much easier to proceed and understand how to improve for next time.

How to Improve Your Learning

A way to improve your learning is knowing how you best receive information. While there is controversy around labeling people as strictly “auditory” or “visual” learners, people will have certain strengths and weaknesses they should be aware of. For example, a student with dyslexia should not rely solely on reading information and should, instead, read along while listening to an audiobook. A child with slow processing speed will benefit from written instructions to refer back to, in addition, to orally given instructions. This is why we strongly recommend multi-sensory instruction because multiple learning “styles” are covered.

Whatever you/your child's learning style is, it is important to be able to understand what knowledge you have and be able to best utilize your studying to learn the other information.