How to Teach Vocabulary Explicitly

Hey! How’s it going?

Today, we wanted to talk about a critical component of your literacy instruction. This particular topic is one of our 5-Core Components of Literacy but often, in the literacy field, we see that explicit instruction on this skill is falling short.

The skill we want to talk about today is…

Vocabulary

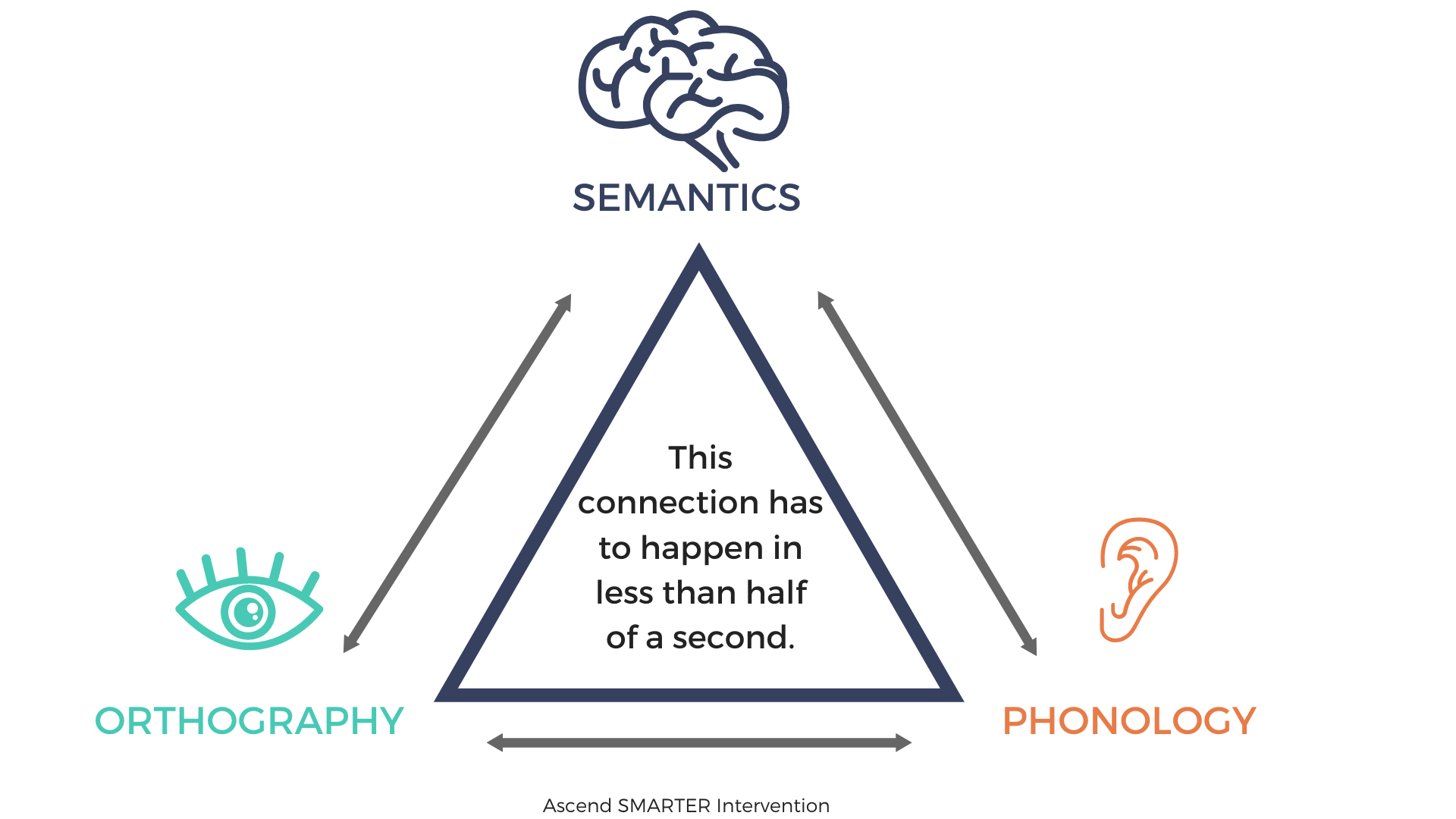

Whenever we talk about literacy, we always come back to this literacy processing triangle. Now, many reading intervention programs do a nice job of connecting the bottom points of the triangle by working on the orthography-to-phonology connection. Much less frequently, we see the third point, semantics, tied into a program. Semantics on its own relates to students’ understanding or making meaning of words (this is where vocabulary comes in).

When we look at the connection between orthography (visual) and semantics, this is where reading comprehension skills lie. Conversely, we know that listening comprehension stems from the connection between phonology and semantics. Semantics and the connections between orthography and phonology are a critical part of literacy intervention that isn’t often explicitly instructed on, so today we are going to explain how to easily and effectively tie semantics work into your literacy intervention lessons.

Why is Semantics so Important?

The ultimate goal when reading is to be able to understand, or comprehend, what the text is saying. As students get older, reading comprehension is a critical skill in order to be successful. Think about all of the independent reading students are asked to complete to get through their classes. Even after students are done with school, we as people rely on reading comprehension every day. Without a proper semantics foundation, this necessary life skill can suffer.

Vocabulary and Semantics

Often, we will see instructional models where younger students begin with phonological awareness, then move on to phonics, and then work their way through decoding and encoding leaving vocabulary (the top point of the triangle) and reading comprehension (the connection between orthography and semantics) until the end of their instruction. This splintered approach doesn’t take into account that the earlier we can support students’ vocabulary and comprehension skills, and the more explicitly we can explain the connections, the better their literacy abilities will be later on.

It’s more than understanding definitions…

So often, vocabulary is taught by giving students a list of words (usually relating to a text) and asking them to find the part of speech and definition. Sometimes, they may also be asked for a synonym/antonym and place of origin. While parts of this approach can be helpful (more on that further down), often students just practice rote memorization and don’t actually understand what the words mean.

Definitions and memorization are not enough.

What we really need to be doing is working on semantic processing from a very early age so we can teach students how to categorize and conceptualize ideas to support comprehension. From the time students are in Kindergarten, we should be supporting semantic processing and their ability to create categories.

Take this activity, for example. As students look through the pictures and select which one completes the category, they are developing their receptive vocabulary. Then, when asked to name the category, they are working on their expressive vocabulary. The ability to recognize the patterns and see what the different images have in common helps with their overall understanding and will help students be able to better comprehend textbooks and other reading later on.

When I work with my middle and high school students, one of the things they struggle with the most is finding the main idea in a passage. This drastically impacts their ability to understand what they are being asked to read. One of the approaches we use to help them find the main idea is to first locate the details. Together, we look and see what the paragraph is talking about. Once we find our details, we need to be able to recognize what they all have in common. The ability to categorize the details is how we find the main idea and gain a deeper understanding of what we are reading.

It has been said before that as students are able to read more fluently (after years of decoding practice), their comprehension will improve because they are spending less time laboring over the words. While this may in part be true, more often than not we are seeing students continue to struggle to understand what they are reading, regardless of how fluent they sound. If students have spent a few years solely practicing how to decode words but are not explicitly taught to connect meaning, their processing and vocabulary knowledge (and in turn, their comprehension) will suffer.

When we don’t support their ability to conceptualize information and make meaningful categories from the beginning of their intervention, we miss crucial years where they aren’t pulling meaning from text. We HAVE to be working on all points of the literacy processing triangle, and all 5 Core Components of Literacy in conjunction if we want to see students actually become fluent readers and writers.

Vocabulary Scope and Sequence

We begin working on vocabulary development with our youngest students and continue throughout their entire intervention journey. Typically with students in Kindergarten and first grade, we practice their expressive and receptive vocabulary skills by asking them to categorize words. Once students reach second grade, we continue with categorization practice but we will also begin working on multiple-meaning words (i.e. rock could be used to mean a stone, a back-and-forth motion, or to describe a genre of music), finding synonyms and antonyms/shades of meaning, and syntax. We continue this vocabulary practice (matching the level of difficulty to the students’ abilities) throughout their intervention journey.

Instead of just copying definitions, do this!

When we work on specific vocabulary words with students, we do not have them just copy a definition. Instead, we first ask them to categorize the words (i.e. it’s an action word, a describing word, a place, a job, a tool, a food, etc). Then, we ask them to give the function or purpose of the word. We continue with a statement where students would say, “It’s like ______________ but ___________________” where they provide a synonym and an antonym or shade of meaning.

Instead of always asking for the opposite, students should use the “but…” to either offer a distinction of how the word is different than the synonym (i.e. a ball is like a balloon but it doesn’t float), or they can offer an opposite if a clear one exists (i.e. hot is like warm but not cold). Finally, students should provide any defining features that will help them understand or recognize the word.

The easiest way to pull this into your lessons…

As you ask students to read their word lists, select a word from there to practice defining using the framework shown above. A great way to add extra engagement here is to make it a game. You can model first by selecting a word and not telling your student which word you picked. The goal of the game is to define the word so clearly that the student can guess which word you picked. Then, they should do the same thing but have you guess.

This is helpful for three reasons. First, it is great practice for students. Second, you can see how students are thinking about the words. I once had a student try to define “aloe” and he started by saying it’s a food. He went on to say it is a jelly-like substance that comes from a plant and you put it on a burn, which was more correct. Through this activity, I was able to see that his categorization of the word was atypical of what I would have expected. We discussed that while aloe is sometimes used in juices and other edible things, that isn’t the best way to categorize it based on how we typically hear about aloe being used. The final reason this is helpful is that you can show students how to take formal, dictionary definitions and put them into the framework above.

So often students are told to “put it into your own words” without ever being explicitly taught how. This is where students often get caught up in rote memorization, learning definitions for a test but not truly understanding the meaning. A week after they take the test, the definition is lost and they haven’t gained any vocabulary knowledge. We encourage you to work with them on words they don’t know. Look up the definitions and help them take the definition and change it into something they can understand. This will help them hold onto that information long-term, instead of forgetting it in a week.

We hope you found these tips helpful! To begin putting these vocabulary concepts to practice, check out the 5CCL Activity Library. This library has hundreds of science of reading-aligned resources that provide targeted practice for all 5 core components of literacy + writing.