The Science of Reading Made Simple: A Guide to Effective Instruction

Let’s be honest.

Reading is hard!

In fact, the human brain wasn’t even designed to read. While there are specific areas responsible for motor planning and speech, there are no specific areas designed for reading. This means that several areas in the brain must work together in order to accomplish this task.

Over the last few decades…

…there has been a lot of research done that helps us understand the brain, how we learn to read, and how we, as educators, can best teach reading. This movement is known as the Science of Reading.

This research has helped us recognize the necessary components of a reading & writing lesson, but, it can feel like a lot to dig through! Many of these studies can feel like they are pulling us in different directions (pair that with the “reading wars” pitting one instructional approach against another and making us feel like we will fail our students if we are on the wrong “side”), and it can feel almost impossible to know what we should be doing.

The solution we’ve found is to really look into the “why.”

If we can figure out “why” we are doing something in our instruction, it makes sifting through the research and differing opinions so much easier because we know what the intended outcome is. This helps us determine why one approach is recommended for one student or group of students and why another student or group of students may need something different.

Let’s break up a few of the key principles and backgrounds of the Science of Reading.

Literacy Processing Triangle

The Literacy Processing Triangle is a great visual to understand the underlying neural connections required to read and write effectively. This triangle framework comes from a computational model used extensively in the study of reading (Seidenberg, 2005).

The idea is that there are three distinct processes that occur in order to understand and use written language (reading and writing). So for example, if we were thinking about the word "bat" we would have three processes involved in order to read or write the word and associate meaning.

1 - The phonology processor

This processor is responsible for interpreting the sound structure in our language and allows us to recognize individual sounds in our language. We start developing this ability very early on in our development. However, this ability continues to expand over time. As we get ready to read and spell we must be able to recognize differences in sounds as well as isolate individual sounds in words. For example, in order to read the word “bat” we must be able to blend the individual sounds /b/, /a/, and /t/. Alternatively, to spell the word “bat” we need to be able to isolate the individual sounds. This processor allows us to "sound out words" for reading and spelling.

2 - The semantics processor

This processor is responsible for tying meaning to our language. Once we hear a word or read a word, we must activate an understanding of the word. For example, if we hear the word “bat,” we need to determine whether we are talking about a nocturnal flying creature, a wooden/metal club used in sports, or an action like “batting” your eyelashes. This is critical for the comprehension of concepts.

3 - The orthographic processor

This processor is responsible for interpreting the visual component of our language. This is a complex process and does not develop until later in our development (usually beginning around preschool). The orthographic processor allows us to recognize the lines and curves we see in “bat” as the letters b, a, and t.

When reading and writing, these three processors need to activate and connect with each other in less than half of a second in order to read or write fluently.

This is the model we ALWAYS come back to when working with students because learning to read and write requires this connection and any possible breakdown in skills is caused by a difficulty in one or more of these processors.

So then…the question becomes, how do we help students learn to activate these neural processors?

Well, great news! In 2000, the National Reading Panel (comprised of a team of experts in literacy, cognitive development, psychology, and on and on) came out with the 5-Core Components of Reading that helped us understand exactly what skills students need to learn to activate this process.

5 Core Components of Literacy

We say literacy because reading & writing are reciprocal processes and both need to be targeted!

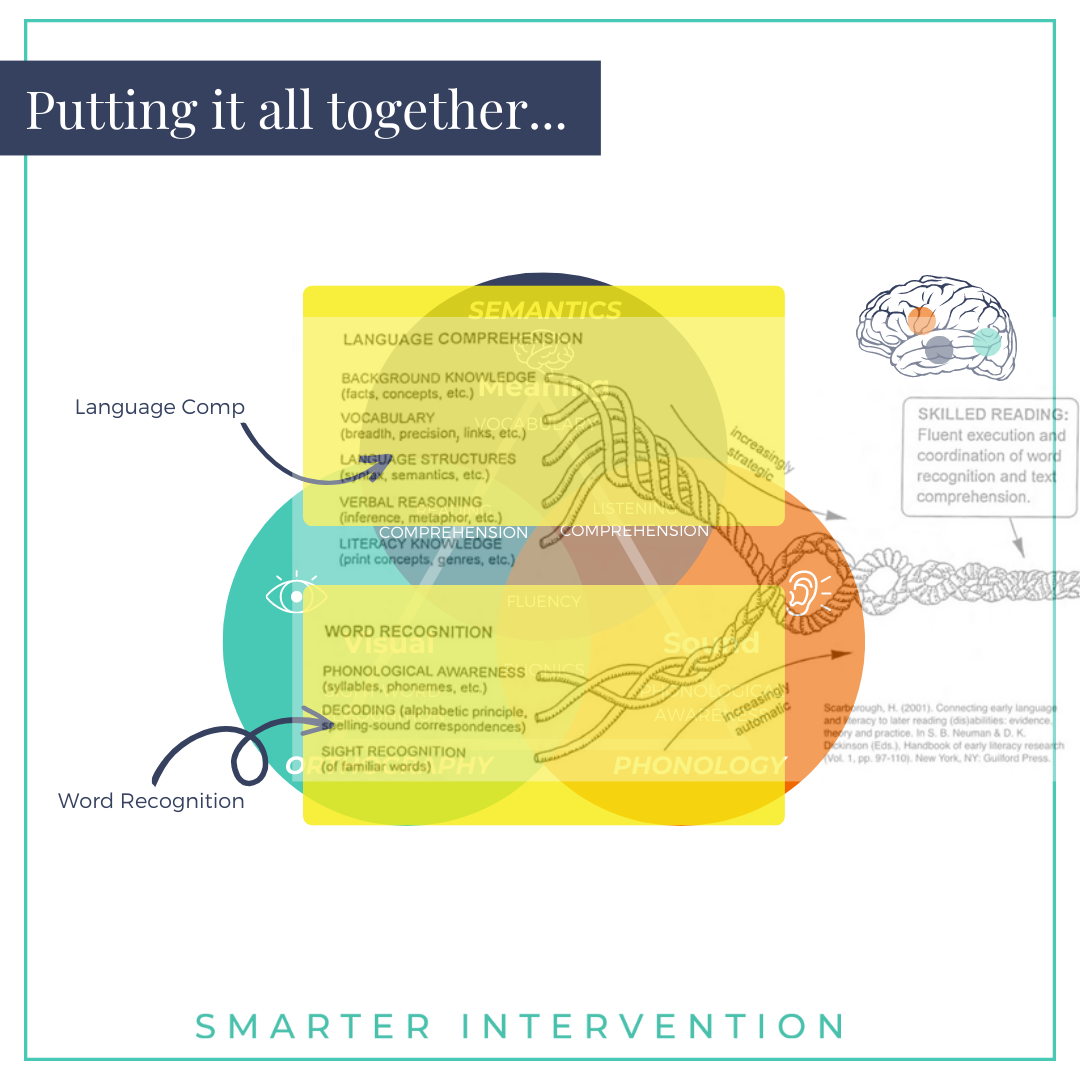

Following a comprehensive meta-analysis, this team of researchers determined that effective literacy instruction needs to target phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, reading fluency, and comprehension. We can map these core components onto the Literacy Processing Triangle and see how everything is coming together.

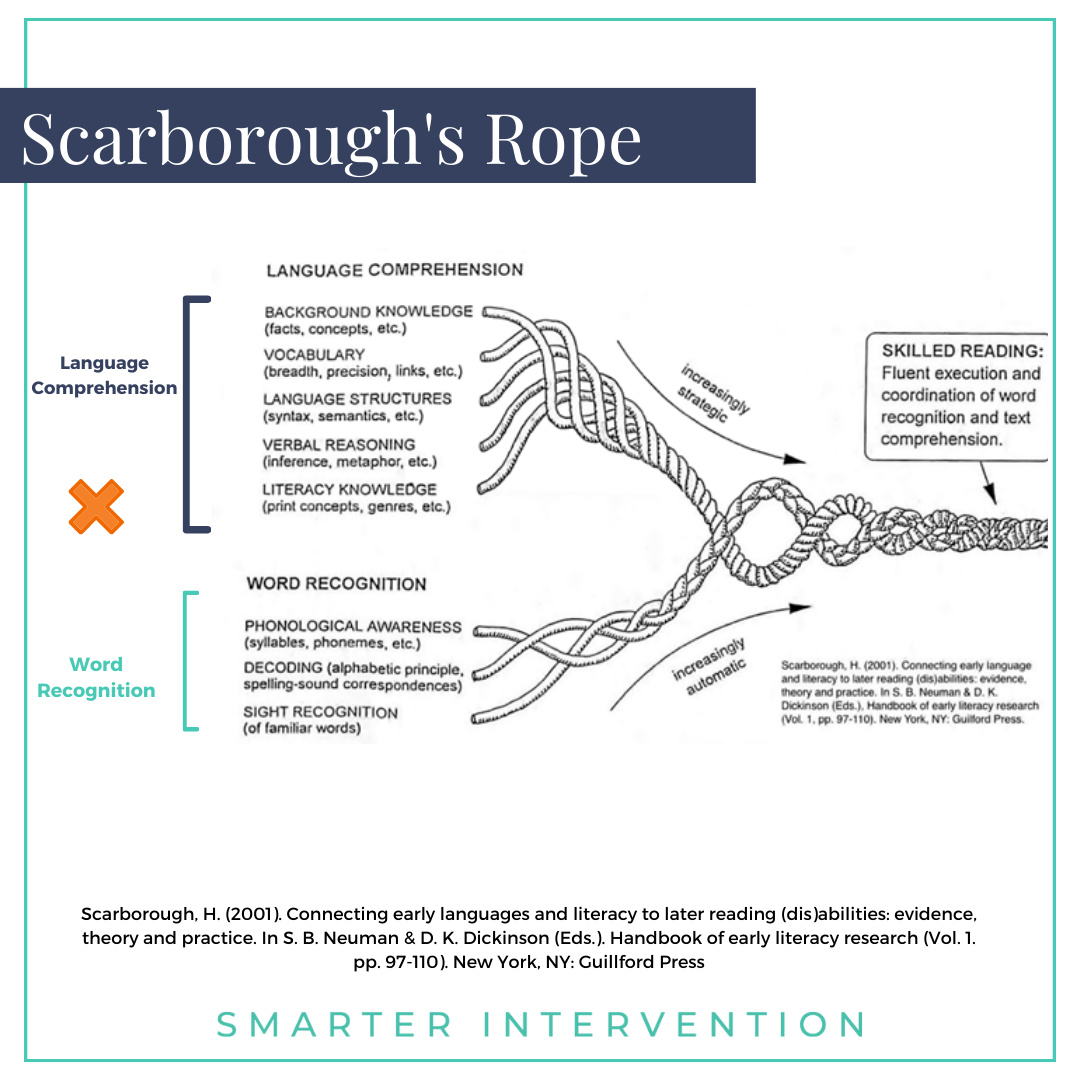

Now, another popular model in the Science of reading is Scarborough's Rope. This rope provides another visual that helps us understand how the reading (and you can see the correlates in writing) processes come together.

Scarborough’s Rope

In 2001, Hollis Scarborough published “Scarborough’s Rope” which stated that reading is comprised of two key components that need to intertwine with one another…

…word recognition (decoding) and language comprehension.

This model basically says that the top of the literacy processing triangle and the bottom need to come together for effective and skilled reading (makes sense!)

The Active View of Reading

Twenty years later in 2021, Duke & Cartwright expanded this “Simple View of Reading” and found that in addition to word recognition and language comprehension, there are bridging processes that students need to use to tie the two together.

This model also introduced “active self-regulation” and executive functioning skills to the mix.

While these research articles are presented slightly differently (which is why it can feel so hard to know which approach to “follow”), they are all saying the same thing.

The Literacy Processing Triangle creates a visual for us to understand the neurological component (the cognitive process) underlying reading ability. The 5 Core Components of Reading (and writing!) map onto the triangle and help us see what type of instruction supports which points and which connections. Scarborough’s Rope & the Active View of Reading bucket these skills and processes so that we can further understand which subskills need to be considered within these larger buckets. Further, they provide a visual to help us think about whether students are struggling more with decoding, language, executive functioning, putting it all together, or a mix of these.

Now - when we learned this, it made our approach to reading instruction a lot clearer.

If we can figure out where students have gaps, it can help inform why our instruction needs to look the way it does.

So, that’s a lot to unpack. To summarize, reading IS a complex process but understanding the bases of literacy, the neurological processors, the two buckets students often struggle with, and the key instructional components can help us set the foundation we need for effective literacy support.

We must question the “why” as we look at instructional approaches because that's how we can continue to put together effective instruction that meets the diverse needs of our students. Each student brings us unique challenges and strengths so to best serve them, we must remain open to ever-evolving perspectives.

For more information, download our FREE SOR blueprint below!

Check out this video to learn more!

Research Citations for further reading:

Duke, N.K., & Cartwright, K.B. (2021). The Science of Reading Progresses: Communicating Advances Beyond the Simple View of Reading. Read Res Q, 56(S1), S25– S44. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.411

National Reading Panel (U.S.) & National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U.S.). (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read : an evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.Scarborough, H. (2001). Connecting early languages and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: evidence, theory and practice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.). Handbook of early literacy research (Vol. 1. pp. 97-110). New York, NY: Guillford PressSeidenberg, Mark. (2005). Connectionist Models of Word Reading. Current Directions in Psychological Science - CURR DIRECTIONS PSYCHOL SCI. 14. 238-242. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00372.x.