The Reading Wars - Who is Right?

Raise your hand if you’ve ever heard of the reading wars.

This “battle” has been a long-standing argument between whole-language and phonics-based instruction. Over the last few decades (as more research has been done as a part of the Science of Reading movement), we have seen the pendulum swing back and forth and back again between these two reading approaches.

If the recommendations change every ten years or so, how do we know which is "right?"

The first thing we need to do is understand how different parts of the brain work together to read and write so that we can assess how these different approaches fit into these cognitive processes.

Let's dive in.

The Reading Brain

The human brain was not designed to read. While there are specific areas of our brain responsible for motor planning and speech, there are no specific areas designed for reading. This means that several areas in the brain must work together to accomplish this task.

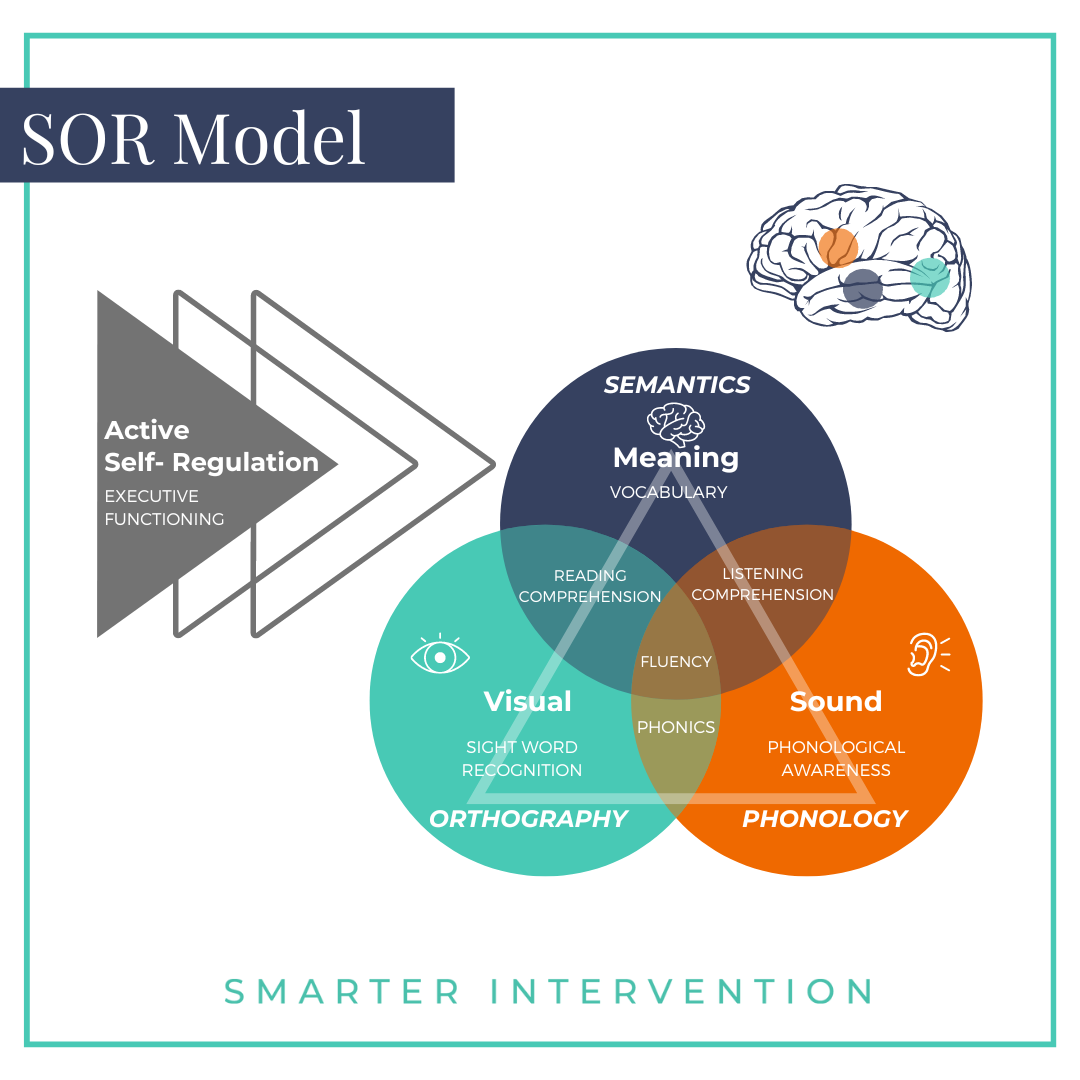

In short, we need the phonology (sound), orthography (visual), and semantics (meaning) processors to activate and connect in less than half of a second to read and write effectively. You can learn more about the reading brain & cognitive processes >>here.<<

Once we know how reading is developed in the brain, we need to look at these two approaches and how they support these different processes.

What does "phonics-based" instruction mean?

In a phonics-based approach, students are taught to decode words based on sound. Often, students work through reading at the sound/word levels and use decodable texts (stories that do not include words with patterns they have not yet been explicitly taught) so that students can rely solely on using phonics knowledge to sound words out.

What are the key components of phonics-based instruction?

In this approach, there is a lot of time spent on phonology (through phonological awareness instruction), orthography (making sure students know what letters look like and how to form them), and the connection between the two (phonics).

who benefits from phonics-based instruction?

Phonics-based instruction is going to be best for students who struggle with phonology/orthography or the connection between the two, but already have strong semantics (i.e., reading comprehension, listening comprehension, and vocabulary).

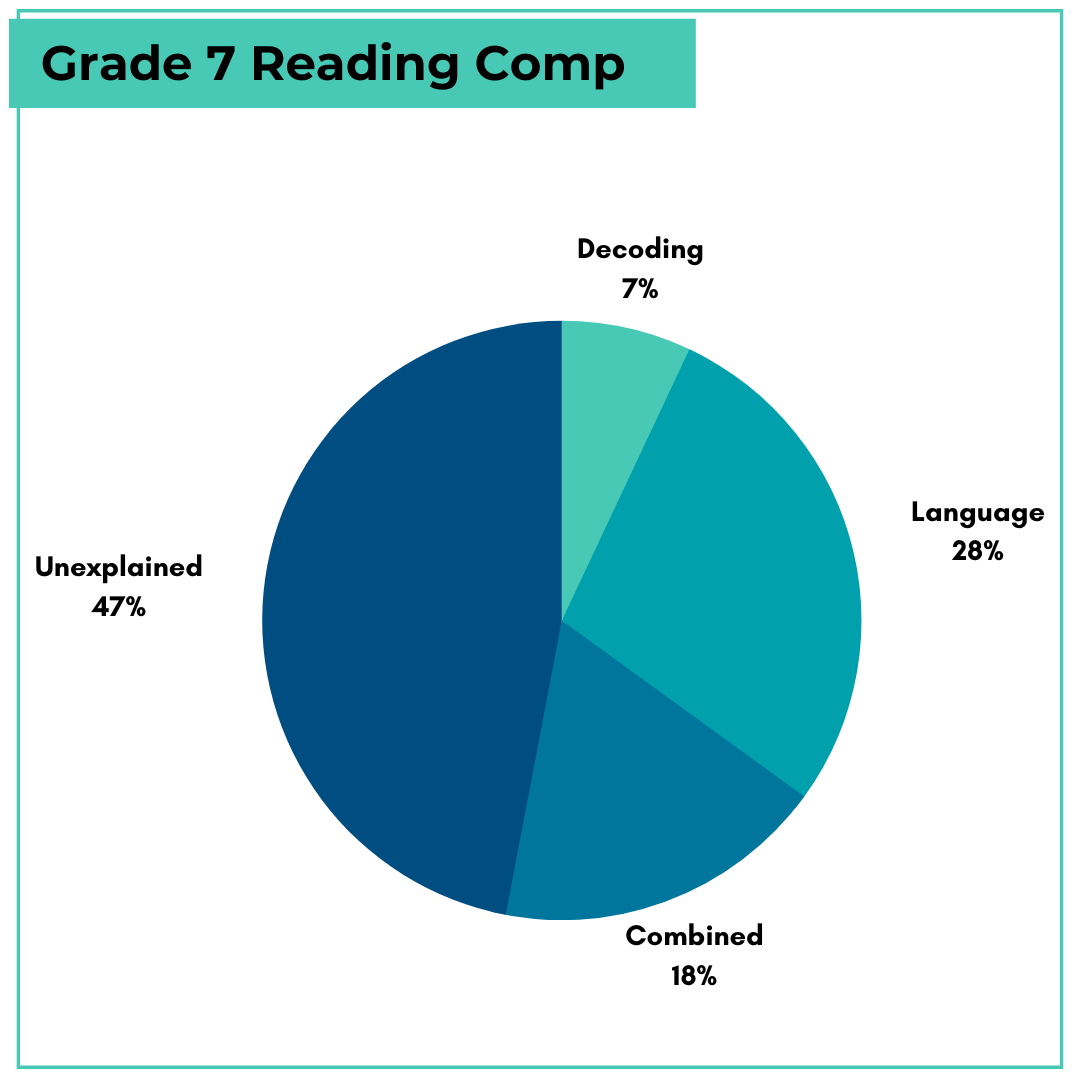

Generally, we see this style of instruction as most effective for students in elementary school. This is NOT to say that there is not still value in providing explicit decoding strategy to students in middle school and high school (there is!) but the percentage of how much decoding ability is impacting a student’s ability to comprehend is decreasing as students get older.

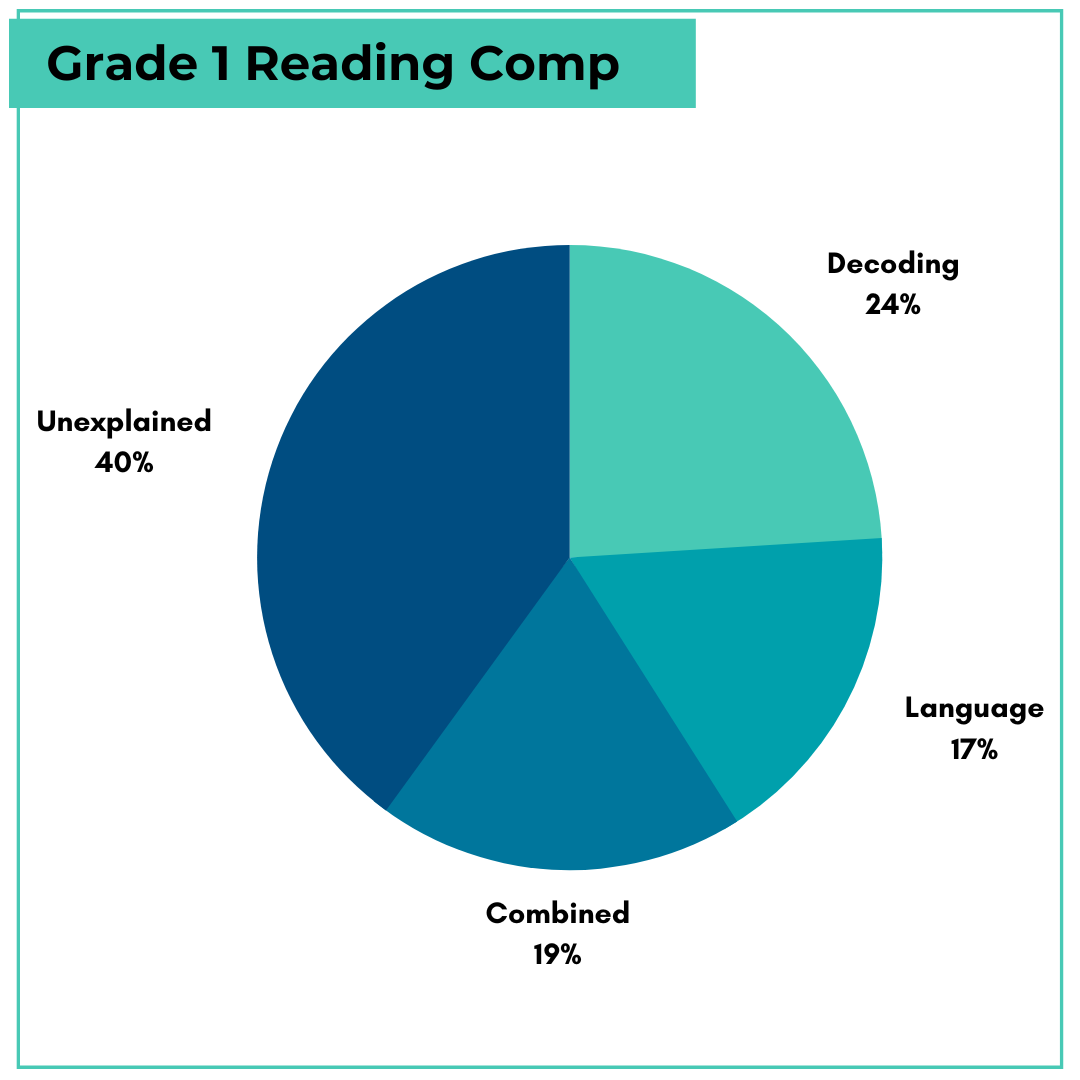

In a study conducted by Formann and Petscher in 2018, it was found that 24% of the differences in reading comprehension could be explained by difficulty with decoding and 19% of the differences in comprehension could be explained by difficulty in decoding and language skills in 1st grade.

You might also be curious about that 40% of unexplained variance…what's that about?! While we can't say specifically what caused that unexplained variance in this particular study, what we can say is that in our work with students, a big chunk of that unexplained variance is likely caused by difficulty with executive functioning, active self-regulation…you know the big gray part of this model.

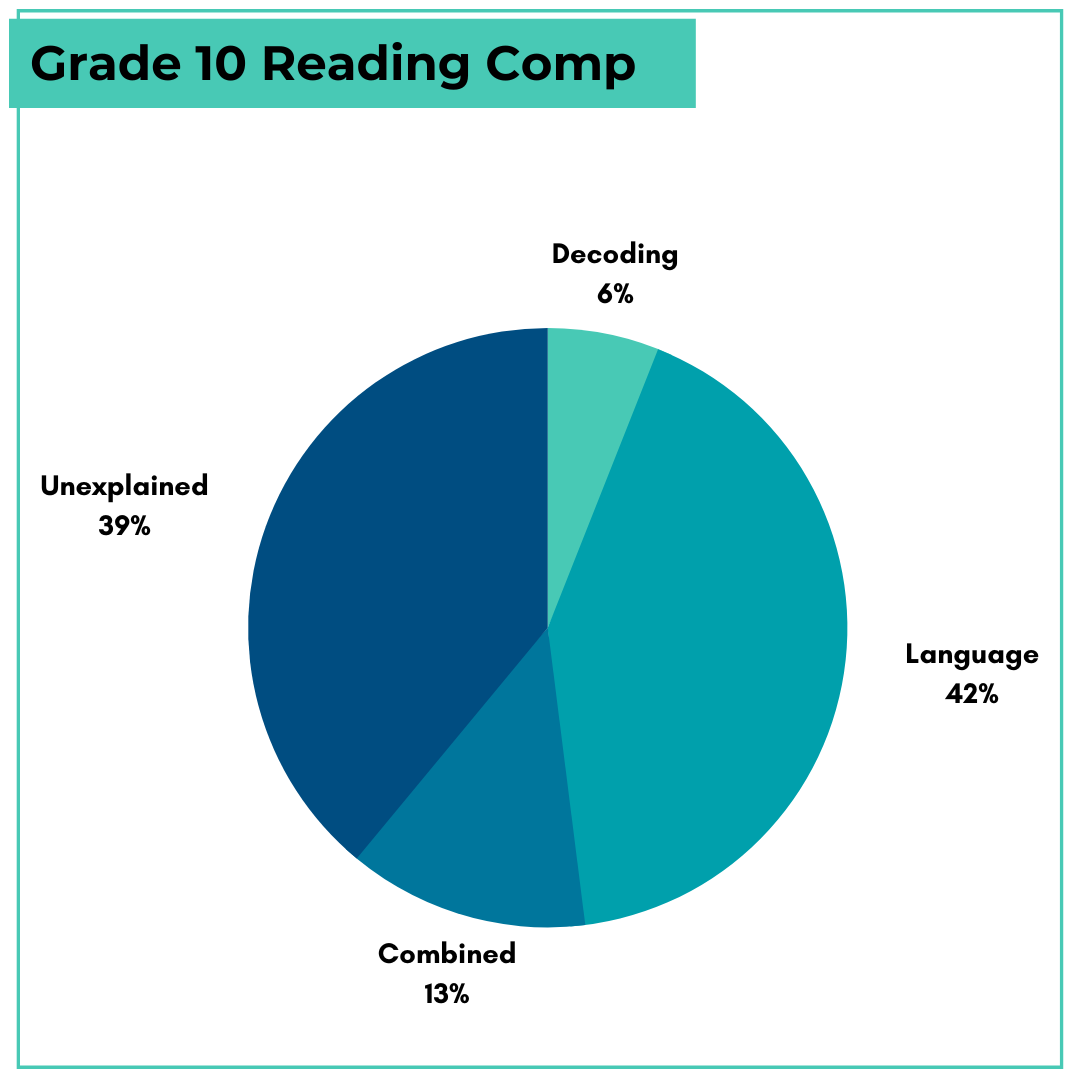

As students progress into middle and high school - that difference in reading comprehension because of difficulty with phonics knowledge and decoding continues to become a smaller and smaller piece of the pie. Specifically, we see 7% of the difference due to decoding difficulty and 18% due to combined decoding and language difficulty in 7th grade. In 10th grade, we see 6% of the difference due to decoding and 13% due to combined decoding and language.

All this to say, as students get older, research tells us that there are higher payoffs for language-comprehension-based instruction than there are for phonics instruction.

What are the downfalls to watch out for with phonics-based instruction?

While phonics-based instruction is a great way to support students' phonics knowledge, it often doesn't account for difficulties with vocabulary and comprehension and lacks application to authentic text or other subject areas. Without semantics support, students' phonics knowledge may improve but it can be harder for them to generalize this progress to settings outside of their literacy lessons. Using only decodable text can also impact student buy-in and generalization as they aren't being shown how to transfer the skills learned in isolation to texts and passages they'd see in the "real world." This is especially true with older students.

So, now that we've talked about phonics-based instruction, let's dive into "whole language."

What does "whole language" mean?

The whole-language approach to reading supports the idea that students should be relying on literature and recognizing "core words" (instead of sounding out each individual sound in order to read). There is an emphasis on meaning in this approach and how words work together to form sentences and passages. A cueing system is used and asks students if the word sounds right in the sentence, looks right, and makes sense in context to help students recognize if they have read words correctly.

What are the key components of a whole-language-based lesson?

Whole language instruction is designed to utilize executive functioning strategies and language comprehension first and foremost, so students can rely on their knowledge of how our language works to support reading.

This approach often gets scrutinized because its lack of explicit phonics instruction means that students may "guess" at words instead of decoding them. While guessing at words is not an effective strategy on its own, using the approach of, "Did the word I read sound right in this sentence based on context?" as a self-monitoring strategy is a way students can use their executive functioning skills to self-monitor their reading, support their vocabulary knowledge, and overall comprehension strategies.

Instructional methods here rely on getting students into text to help them build background knowledge. It targets comprehension skills like making connections, inferring, making predictions, cause & effect, and so on as these skills rely heavily on our overall understanding of language and what we are reading. It also supports self-monitoring, as students will be asked, "Did that sound right?" as they are reading the text.

who benefits from whole-language instruction?

Students who already have solid phonics knowledge but need self-monitoring and executive functioning support will benefit from this type of instruction. It can also support students struggling with meaning (the semantics part of the Literacy Processing Triangle), as it will help them identify what isn't making sense to them (either it didn't sound right as they read it or they are unfamiliar with what a word means). Once they recognize what doesn't sound right, additional instruction on how they can then figure it out is recommended.

What are the downfalls to watch out for with whole-language-based instruction?

Because there is very little explicit instruction (and certainly not systematic instruction), if students don't have a solid foundation in decoding/encoding (meaning they can't sound words out for reading AND spelling), this style of instruction is going to miss a big piece of what students need.

We should also consider where students might have a breakdown between, "Did what you read sound right?" and actual strategies for error correction. Self-monitoring will be the first step but we need to make sure students are taught strategies to help them then define words, figure out comprehension questions, and so on.

So...which is better? Phonics-Based Instruction or Whole-Language?

As we continue to learn and progress, popularity for one model over another seems to swing like a pendulum. Well-intentioned educators often pick one “side” and state that they are aligning with “what the research says” and if you don’t agree then you’re wrong.

Here’s the thing…

Phonics-based instruction isn’t “right,” whole-language isn’t “wrong,” and vice versa.

Phonics-based instruction supports the bottom of the literacy processing triangle and whole-language supports the top & active self-regulation.

The "Reading Wars" have pitted sides against each other in support of one approach or the other instead of being open to the idea that some students will respond well to one approach and others will need something different.

Instead of choosing a "camp" and sitting firmly in it…

…we should be looking at our students and where they struggle to decide what style of support they need. We like to use this grid to understand where students need the most support.

Students who are struggling with word recognition will benefit from phonics-based instruction. Students in the comprehension difficulty section will benefit more from instruction in strategies to answer comprehension questions, define vocabulary words, and build up a knowledge of language & meaning (what whole language could be if we expand past the initial self-monitoring tasks). Students with weak word recognition AND comprehension need both.

If you're working with individual students, you can use this grid to help you determine the best course of action for each child. If you are in the classroom, you likely have students in all four of these quadrants. The easiest way (at least that we have found!) to make sure that you are supporting everyone is to use a phonics pattern as a through line while targeting PA, phonics, vocabulary, reading fluency, and comprehension, while also teaching self-monitoring strategies (essentially taking the best parts of both approaches) in each lesson.

Instead of listening to the constant back and forth of “whole language” vs. “phonics-based” instruction or all of the different suggestions coming at us from every direction, we need to be asking “why.” Why is this approach suggested? Why am I not seeing results with this? Why is this working for me, even if other people say it didn’t work for them? Why ISN'T this working for my kids when it worked for others?

When we know why (instead of just implementing the “how”), we can truly cut through all of the noise and confidently reach each child.

So, in the battle of "phonics-based" versus "whole-language," nobody really "wins."

In fact, taking a narrow focus means that we might help a few students and get them fantastic, life-changing results, but we also risk missing a number of other students who need a different approach. Both approaches do some things well and completely neglect other areas of the literacy processing triangle.

We always say, "There are many roads that lead to Rome." Instead of focusing on the battle between approaches, our hope is that educators will look at the students and let the students' needs (not the most popular podcast, the newest article being shared, or a trending blog post - yes, even this one!) guide their instruction. If we know why our students are struggling (i.e., if they are struggling with the top of the literacy processing triangle, the bottom, or a combination of both), then we know why one approach will be better than another.

Since students need to connect that whole triangle to read and write effectively, we need to look at where they are struggling and build the processors and connections they are missing (while also showing them how those connect to the processes they may already have).

For more information, download our Science of Reading Blueprint >>here.<<